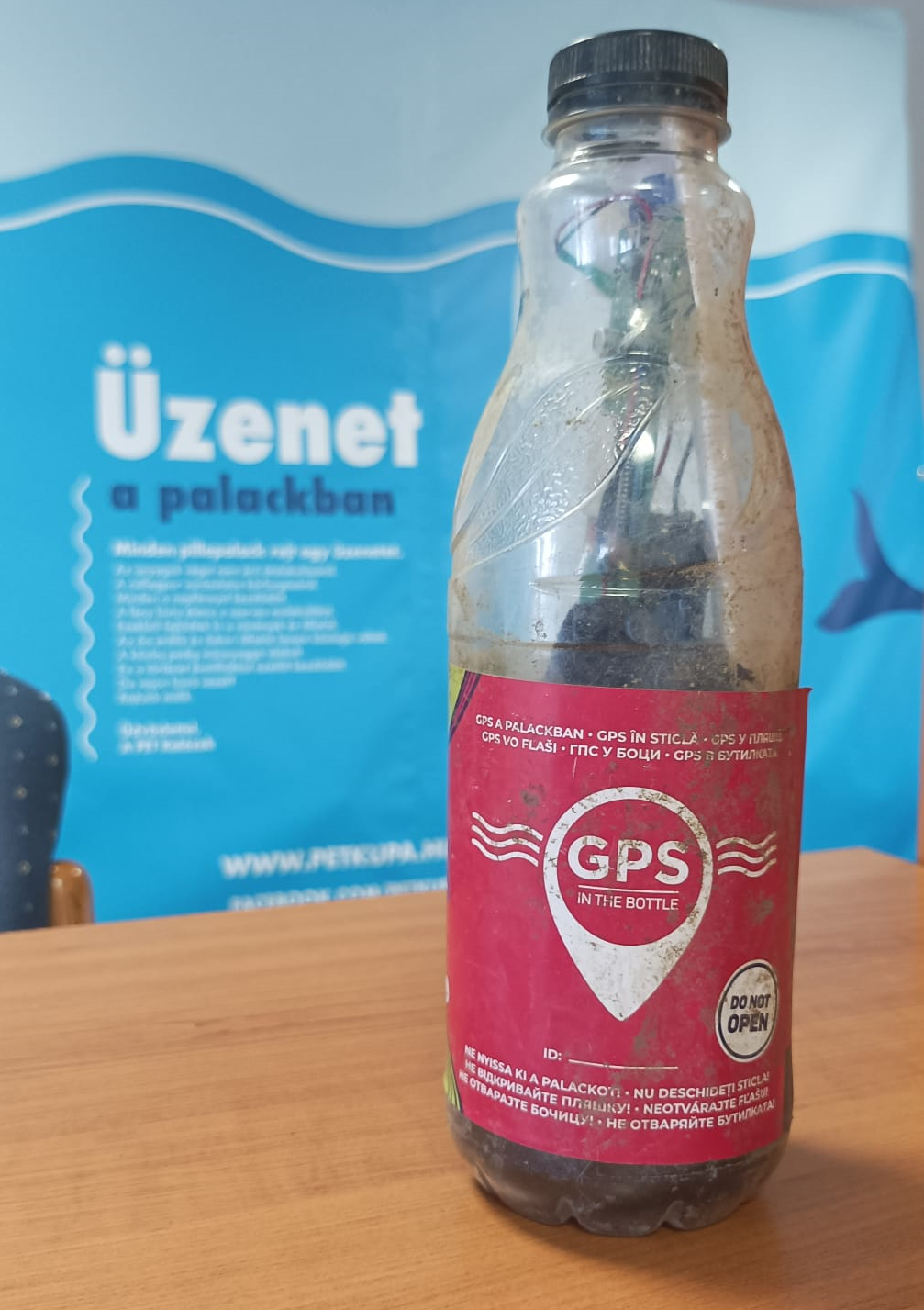

In addition to collecting, sorting, and processing floodplain waste, the Tisza Plastic Cup also studies plastic pollution in the river. If we know more about the behaviour of river waste, clean-up actions can become even more successful. On 7 January 2022, Plastic Cup river rescuer Krisztián Berberovics took advantage of the rising tide and released bottles equipped with GPS transmitters at two different locations.

“How fast do bottles travel on the flowing rivers, how far can they travel in a given time, and where, why and for how long do they get stuck?,” asked Plastic Cup scientific expert Miklós Gyalai-Korpos, listing the questions that transmitter bottles are expected to provide answer for.

The answer is far from obvious. While according to popular belief there is no reason to mark bottles as they will "float to sea anyway", Plastic Cup volunteers know from the bottle mails they have collected over the past ten years that this is not the case. But to convince the scientific community, the public, and the experts, it is not enough to refer to a decade-old Ukrainian message in a bottle found in a Hungarian floodplain, it requires thorough research. For two years, participants of the Zero Waste Tisza River project has been marking bottles using a variety of technologies. While the previous marking methods were more about overcoming technical challenges, the developments now ensure that data is collected continuously and reliably. Last time, two transmitter bottles were released on the river. The first one was thrown into the main current of Tisza river at Tivadar, and the other into the Bodrog river at Alsóberecki. They released from the bridge closest to the border in both cases, as this is the only way to drop the bottle into the main current during flooding. “Ever since the bottles are on their way, not a day goes by that I don't check where they are,” said Gergely Hankó, the man behind the idea of the marked bottles. “Their behaviour is very interesting and revealing, and we hope that they will confirm our hypothesis about river waste in the long term."

The Bodrog bottle didn’t get far; it stuck for days under Sárospatak, at a plastic dump well known to plastic pirates. It floated on eventually but got stuck in another floodplain. This is important data, as two other marked bottles got stuck in the same section of the river during last January's experiment. The data from the Clean Tisza Map confirms that floodplain pollution is even worse than average in these places.

Meanwhile, the Tisza bottle has been moving at breakneck speed, which can be followed in real time on the Zero Waste Tisza River project website, supported by The Coca-Cola Foundation. The GPS bottle made its way to Tokaj in one day, stayed longer in two places (above Tiszafüred and then at the entrance to Abádszalók bay), and after a week and about 300 kilometres, finally stopped at the Kisköre dam. The fact that it hasn't got through the dam proves that it is a real barrier protecting the lower reaches of the river from pollution. During floods, the Kisköre dam can hold up to 600 cubic metres, around 6,000 tonnes of waste.